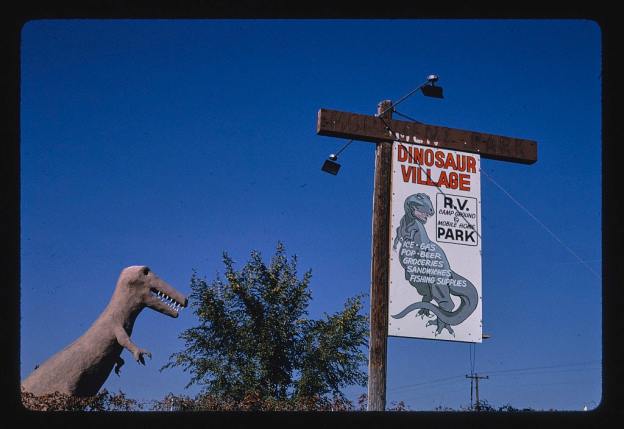

The Library of Congress has just entered some 11,000 photographs of roadside attractions, gas stations, old buildings, and other obscured American novelties into the public domain. It’s a testament to the camerawork of architectural critic and photography John Margolies, whose life’s work was to criss-cross the country over the span of decades to capture these monuments and icons, rendered in an odd, almost funerary style (he would only take a photo if he could “capture the subject in full sun with a cloudless sky, with no people in the frame”, says one write-up). This is, in a way, fitting: Baudrillard never tired of describing America as a land of disappearance—a twist on Deleuze’s own appraisal as the nation as one founded on escape—and these things are themselves vanishing into time. What few remain are reminders of the now-long past moment of the automobile, the Fordist assembly line, and the culture of generic nomadism that these called into being.

Margolies’ photographs span a spectrum of styles and forms, running from New Deal-era buildings constructed in the WPA Moderne mode to the art deco flourishes of small-town theaters, but what interests is the most is the sort found above: the ramshackle, folksy, and un-finessed kind of expression that eludes easy classification. It comes close to what since the 1970s has been described as art brut or ‘outsider art’, but this labeling has only ever been a retrograde sort of typology that works only from within the cozy confines of the artistic canon—where things have been entombed within the cultural mausoleum. By extending its reach to what is deemed outside it—manifested, in a round-about way, as something pathological that is now deemed acceptable—the vibrancy and life of these kinds of expressions undergoes conversion into the quiet stillness of capture.

These things also converge on the territory of kitsch, and in this sense collide with the discourses around postmodernity. Kitsch, per the analysis offered by Frankfurt School thinkers like Adorno, is the inevitable byproduct of mass-scale industrial society. The term itself is likely to derive from the German verb verkitschen, “to cheapen” or “to make cheap”, and for the intelligentsia, its arrival in cultural history signaled the erasure of the gulf between ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms of art.

Jameson, in Postmodernism, describes postmodernity as exhibiting a particular ‘populist’ aesthetic sensibility. Whereas once the “high modernism” of a Le Corbusier or a Ludwig van der Rohe reigned, there was then a sudden shift towards the

‘degraded’ landscape of schlock and kitsch, of TV series and Reader’s Digest culture, of advertising and motels, of the late show and the grade-B Hollywood film, of so called paraliterature, with its airport paperback categories of the gothic and the romance,the popular biography, the murder mystery, and the science fiction or fantasy novel…

The vanishing line between ‘high’ and ‘low’ is indicative of postmodernity’s prime characteristic, the “loss of historicity” that sees all distinctions marked by time and space smeared across a singular social field. This loss carries with it a regressive side, felt most immediately in the sense of an all-encompassing stagnation; this sensation frequently carries with it an active eschatological element rendered in a profane negativity (apocalypse without the light of salvation). But there is a flip side here: with the vanishing of history the actions and cries of ten thousand generations no longer pound in the heads of those living in the present, and what was once action in the strong sense of the word can be replaced by idiosyncratic forms of cultivation. The site of this ‘new’ work is the surface, now freed from the grasp of the depths (because depth is always a matter of history). Beyond high and low, time and history, the very distinction between surface and depth becomes troubled and undermined. At this point, more than ever, does the statement “Deeper than any other ground is the surface and the skin” ring true.

The play of the surface is pure expressive texture, and in relation to the geography of the American landscape, this is exactly what the kitschy roadside attraction and weird building, sculpted by the hands of a legion of anonymous, sloppy craftsmen, is all about. It’s also what is at stake in surrealism. As Deleuze implicitly suggests in The Logic of Sense, surrealism is the overcoming of sense and nonsense at the level of the surface—and there is something profoundly surreal about these concrete and paper mache teepees, igloos, oversized animals and humans, dinosaurs, cartoonish depictions of pioneers and malformed (bordering on the grotesque) businesses and dwelling places. If the vital impulse of the modernist avant-garde was to overcome the distinction between daily life and the art-form—”Let’s not look at a De Chirico painting; let’s live in one”—then this has been realized in this squishy underside of Fordist mass culture, even if it was the first blast of the postmodern mode.

Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, of both the I.W.W. and the Chicago Surrealists, wrote of a buried tendency flowing beneath American culture that they dubbed ‘vernacular’ or ‘everyday surrealism’. Their description, which captures something approach pop art without its elitist or commercialist pretensions, directly presages Jameson’s “‘degraded’ culture” beyond the high/low distinction:

…true poetry surfaced far more often in odd corners of popular culture: in comics (from George Herriman’s Krazy Kat to Walt Kelly’s Pogo), in films (from the silent comedies to the Marx Brothers and Veronica Lake and beyond), in the animated cartoons of Tex Avery and others, in such wildly independent eccentrics as Simon Rodia (creator of the amazing towers in Watts, California), Mary MacLane of Butte, Montana, and the fantastic IWW writer T-Bone Slim (sometimes called the Lenny Bruce of the labor movement), and of course in that inexhaustible fountain of inspired and inspiring poetry known as the Blues.

Paul Baron, himself a member of the Chicago Surrealists, took up this last point in his 1975 book Blues and the Poetic Spirit. In the words of surrealism’s most vocal proponents, the form (like dada before it) took its cues from Freud’s discovery of the unconscious; their goal was to liberation it from its chain in the depths, and let the imagination ‘claim its rightful place’. Baron found this same dynamic at work in blues more generally: the music worked by way of symbols and dreamscapes, serving as the place where that which is repressed in daily life could move to the surface. There is a line, non-existent but nonetheless real, that connects Tristan Tzara to the blues—”phantoms, magic, sexual liberty, dreams, madness, passion, folklore, and real and imaginary voyages”.

There is also a line between the blues as surrealist art and the content of folk music more generally, which Greil Marcus has described as the expression of the “old, weird, America”. The artifact that allows Marcus to open the door to this continuum, obscured and buried in its own right, was Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. Like the roadside attractions, this compilation of rare tracks, cob-webbed by layers of hiss and crackle, erupted right in the heyday of Fordism. Published in 1952, it was flanked by a succession of works diagnosing the strange, new and unpleasant character of the time: Whyte’s Organization Man, Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, White Collar and The Power Elite by Mills, Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders.

Smith’s work, featuring Robert Fludd’s ‘Celestial Monochord’ as its frontpiece, pointed to something entirely contrary to world that these books were describing. Marcus likens it to Benjamin’s Arcades Project by taking up Susan Buck-Morss’ point that the goal was to “accomplish a double task: it would dispel the mythic power of present being… by showing history and modernity in the child’s light as archaic”. The American Folk Anthology did just this by resurrecting the ghost of the ‘archaic’ and the ‘primitive’ in order to explode the plastic, air-conditioned and well-regimented world dominated by pseudo-collectivist corporations and the military-industrial complex. Smith, with deep roots in hermeticism, no doubt saw the records as something of an alchemical working, though the raw materials of this arcane experiment were the lingering traces of “minstrel troupes and medicine shows”, tent revivals, rail-riding drunkards, miners down at road’s end, the outlaw, the revolver. Each track is an outpouring of the symbolism and superstition that colored (and continues to color) America-life. The song “Fatal Flower Garden” describes a boy lured to his doom by a woman bearing in her hands apple seeds, golden rings and diamonds; “I wish I was a Mole in the Ground” expresses a desire to transform into a variety of creatures and the fear of the “railroad man”, who will “drink up your blood like wine”. Bob Dylan would later take up this line, and advance the imagery into even odder territories in “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again”, found on his 1966 album Blonde on Blonde:

Mona tried to tell me

To stay away from the train line

She said that all the railroad men

Just drink up your blood like wine

An’ I said, “Oh, I didn’t know that

But then again, there’s only one I’ve met

An’ he just smoked my eyelids

An’ punched my cigarette”

Oh, Mama, can this really be the end

To be stuck inside of Mobile

With the Memphis blues again

If what is retroactively taken as folk music describes everyday life, it is an everyday life that exists without distinction between itself and dream—an evening realm of phantasy.

If this continuum that transcends time and space, heterogeneous fragments woven together into a common cloth, is indicative of a ‘vernacular surrealism’, then the varied signifiers, symbols, and inexplicable meanderings (occurring at various points as music, painting, the written word and built environment) are the scattered hints and clues of the great unconscious mind at work. Whose unconsciousness? That of the “silent majorities”—not the silent majority of Nixon—or today, Trump—but the one that evades statistical classification and political legibility. But if these ‘majorities’ are silent, it is only silence in the sense that they cannot be directly seen—yet clearly they have a voice.

follow the pinhead

https://www.zippythepinhead.com/pages/aazipreal.html

LikeLike